We live in a world smoothed and straightened by human hands. From the rigid geometry of skyscrapers to the sleek, featureless screens we stare at daily, flatness has become a silent dogma of modern design. It’s a universal concept so ingrained in our lives that we rarely question it—yet this obsession with uniformity reveals a deeper tension between human ambition and the natural world.

Flatness is a paradox. We perceive it as simple and static, but it’s an illusion. Run your hand across a table, phone, or ceramic plate, and the flatness dissolves. What remains is texture, weight, and subtle curves—traces of a material’s origins. Flatness simplifies reality into something manageable, but in doing so, it strips away the sensory richness that connects us to the physical world.

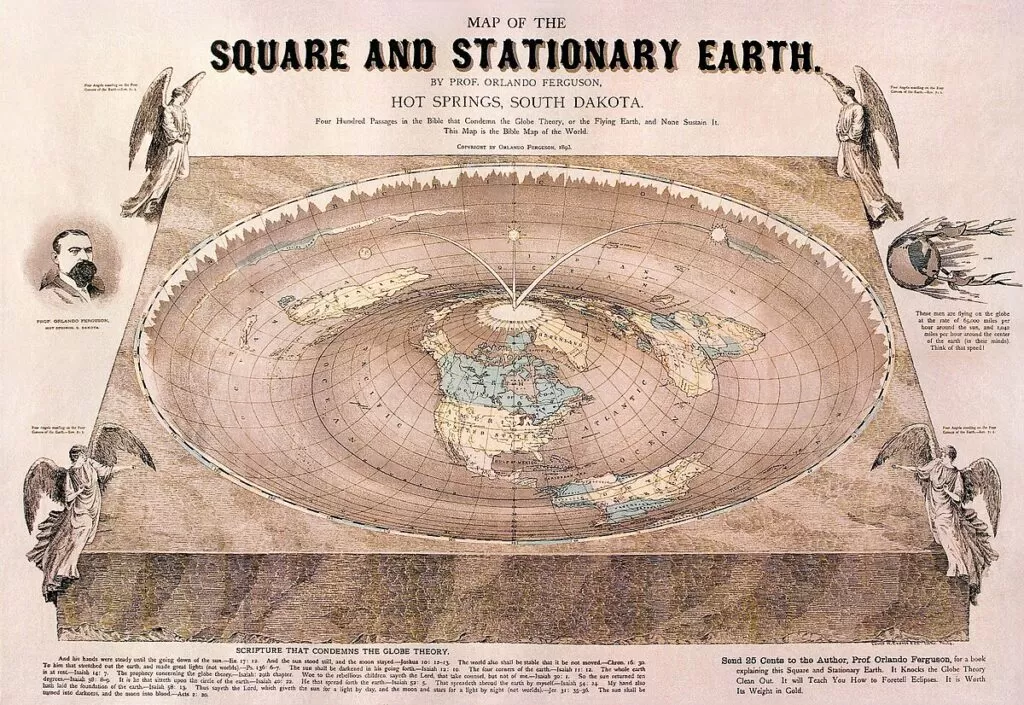

This pursuit of flatness is, at its core, a pursuit of control. We pave roads to erase terrain’s unpredictability, plot cities on grids to dominate organic landscapes, and mass-produce identical gadgets to neutralize nature’s irregularities. Flatness thrives on invariance—a refusal to accommodate quirks of material, body, or environment. But this obsession comes at a cost. By stripping wood of its grain, stone of its texture, or clay of its raw edges, we create sterile objects that feel detached from their origins. A plastic chair may be perfectly uniform, but it will never mold to the body like a hand-carved wooden stool. Even faux wood grain printed on laminate floors mocks nature’s complexity, reducing it to a flat aesthetic.

Nature, after all, abhors flatness. Rivers meander, tree branches fork asymmetrically, and human skin wrinkles with life’s stories. These “imperfections” aren’t flaws—they’re proof of adaptation and resilience. Yet we design kitchens with flat handles that strain wrists, knives that prioritize sleekness over grip, and tables so polished they feel cold. Flatness promises efficiency but often delivers alienation.

The best designs don’t fight nature—they collaborate with it. Think of a mug’s handle shaped by a potter’s thumb, a cutting board carved to guide a chef’s motions, or a chair whose curves mirror the body’s contours. These objects aren’t just functional; they’re *felt*. They honor materials like wood, clay, or metal by letting them warp, slump, or tarnish in ways that tell a story. A knife becomes a dance of weight and balance, not just a sharp edge. A tabletop reveals the knots and ripples of the tree it once was. This is a design that listens rather than imposes, turning asymmetry, texture, and irregularity into virtues.

Flatness isn’t inherently wrong—it’s just incomplete. The challenge is to see it as a starting point, not a goal. Let materials breathe. Let sunlight warp a room’s mood. Let clay crack. Design becomes meaningful when it embraces the irregularities that make us human.

The next time you hold an object, ask: Does it shrink from your touch, or invite you to connect? Does it hide its origins, or proudly display them? The answer might change how you see the world—not as a flat grid to conquer, but as a living landscape to engage with.

In the end, good design isn’t about mastering materials. It’s about listening to them.

No comments.